By Kevin Gilvear

When Pink Films ceased shooting on 35mm just a couple of years ago, it appeared as if the pink industry would take a massive hit; these were sure-fire money spinners, financed with relatively low budgets, filmed within a matter of days and put out quickly across a limited selection of theatres. With companies such as Okura Pictures making just 36 features a year, it was unknown at the time just how much the newly-proposed shakeup would affect future productions, what with up to a third of their budgets now being slashed. However, in the short space of time since the decision was made to shoot digitally, the Pink scene has not so much fallen into disrepair, but rather has managed to usher in something of a renaissance, with distribution company Pink Eiga signalling that we may well be witnessing the beginning of a “Pink New Wave”.

In light of such a declaration, this does make a degree of sense. The shooting format for Pink Films had always allowed for a certain amount of artistic freedom to be had, as long as the required boxes were ticked off within each screenplay. This sense of freedom clearly hasn’t changed in the years since. Directors and cinematographers are now no longer restrained by single-takes, which was once dictated by how much film they actually had assigned to them. Arguably, this newfound flexibility has seen filmmakers become more experimental, not only in terms of capturing unique aesthetics, but also allowing for their actors to wring out better performances.

To support this theory further, I’ve decided to take a look at three recent examples of Pink Films shot on HD formats.

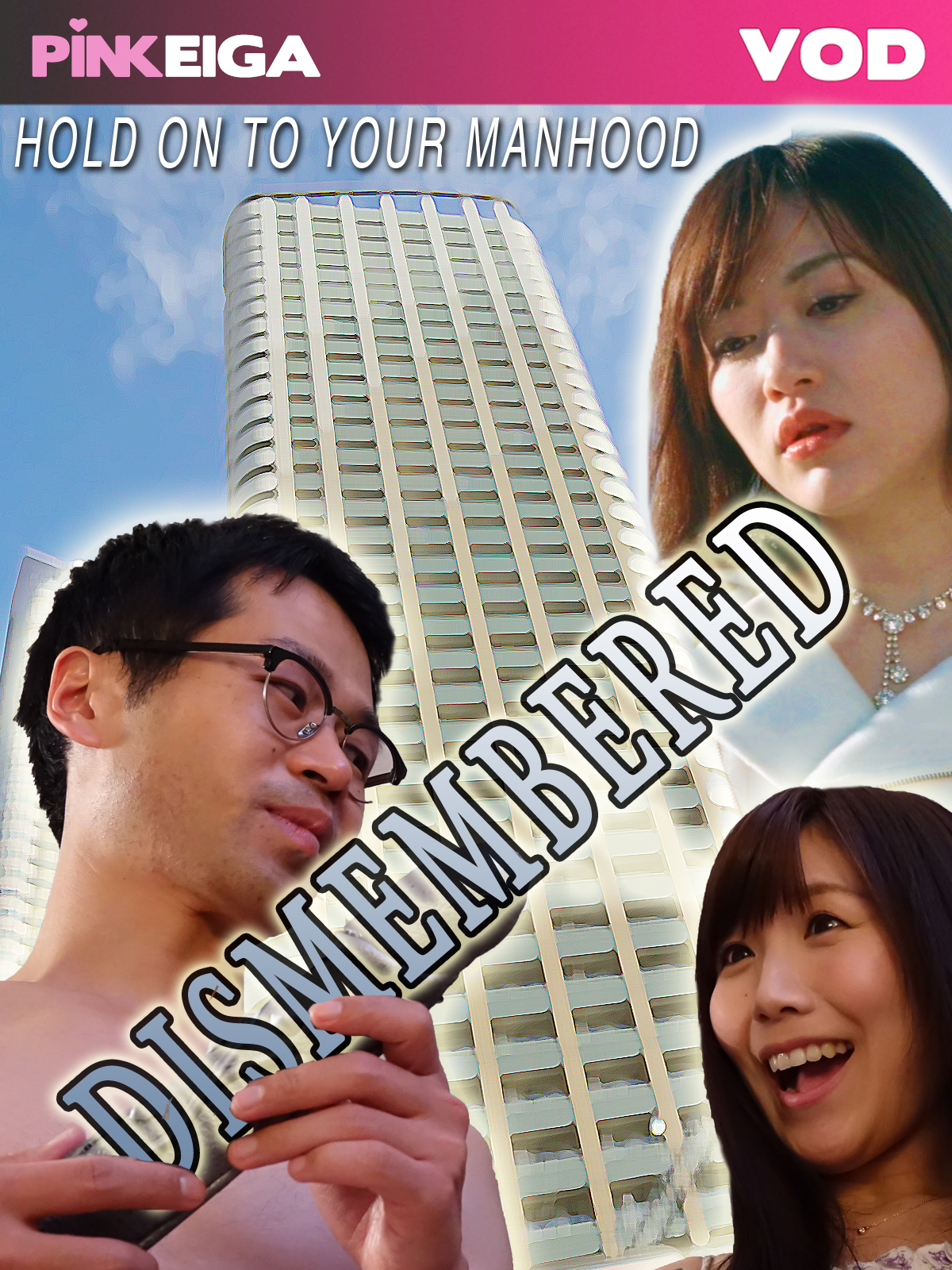

In Minoru Kunisawa’s Dismembered (the barely translatable Tosui tsuma: Hakudaku ni nureru yawahada [Ecstasy Wife: Soft Skin Moistened with Turbidity), we follow psychiatrist Takuya Kuga (a debuting Goro Shimizu), who wakes up in an apartment belonging to a mentally unhinged young woman by the name of Aya Misawa (Ito Yoshikawa). After learning that she drugged him, Takuya is then forcibly raped, before the lass slices off his “member” and enjoys it with a nice chianti. Lying in his hospital bed, Takuya’s wife, Shiori (Saki Mizumi), informs him of a surgical procedure which will restore him to his former glory, and then some! Six months later and the surgery is a success; Takuya’s willy has now reached legendary status, which in turn re-ignites a passion which for years had been thought lost. All’s well it seems, that is until Takuya starts to experience strange visions of a woman, not only in his dreams but also throughout his day-to-day life.

Written by Yuta Takahashi, Dismembered features one of those hooks which seems so ripe for a Pink Film that it’s a wonder why we’ve waited this long to see it. Unsurprisingly, however, given the genre’s penchant for adapting and/or parodying existing novels and acclaimed mainstream movies, here we’ve an alternative take on a story originally written by novelist Keigo Higashino, which was subsequently turned into a motion picture in 2005: Henshin, starring Hiroshi Tamaki and Yu Aoi. While that movie delivered the prospect of a man who undergoes a life-changing brain transplant, which soon turns violent, Dismembered delivers the prospect of a man who undergoes a penis transplant, which soon turns violent. Yes, it’s as daft as it sounds, throwing logic entirely out of the window, while going on to question whether or not love is taken at a superficial level, or truly from within. While the premise does remain light, it ticks along nicely as revelations unfold.

Kunisawa certainly brings to the film an assured sense of direction, though. From the get-go, his 70-minute feature presents itself as if it were a fly-on-the-wall piece; almost every frame of the entire film has a guerrilla feel, whereby we’re taken through each scenario as if we were actually present in every scene. There’s a subtle hand-held charm here, which occasionally blends with short dolly tricks as we follow Takuya and his wife throughout their daily activities. Placing this to one side, the film’s direction truly comes in to its own when our characters engage in sexual activity. Kunisawa employs every trick in the book in order to differentiate each encounter on screen; from using considerably low angles – which also strengthens bouts of tension at key moments – to shooting in as many lengthy single takes as possible, with a welcomed freestyle mentality. It doesn’t always work; one of the weaker aspects involves a couple of spots of fellatio, shot from a POV perspective, which although very cheesy in execution, is certainly admirable.

In the first of two films for this piece from director Hideo Sakaki, 2015’s Naked Desire (Onanie Sister Tagiru Nikutsubo) (read my full review HERE), things become a little more subtle to the untrained eye. At close to 90 minutes in length, not only is Naked Desire ambitious in stretching out its premise of a young social worker (Shou Nishino) who changes the lives of a small band of people, whose paths have converged by happenstance, but so too does it have the feel of a grander picture, one which looks as if it betrays the small budget it invariably had. Perhaps it’s the open setting, which takes place along a seafront, where everything is quite literally bright and breezy, with natural light pouring into almost every frame. Or, it could be the way in which it transitions from scene to scene, making its mark from the opening minutes, with confident establishing shots and skillful editing. Whatever the case, it brings an unwavering polish to it, which engages throughout most of its run time.

Hideo Sakaki, better know for acting in mainstream hits such as Versus, Alive and Battlefield Baseball, arrived on to the pink scene a good few years after directing a number of positively received dramas for mainstream distribution. This is a little more unusual, then, when considering that several prominent Japanese directors, who are still at the top of their game today, (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Yojiro Takita) had their starts in the pink industry. Perhaps then, this seasoned approached toward making Pink Films can be considered more advantageous. Regardless, at this point there’s no real looming threat that the genre and any of its artistic integrity is showing any signs of dying out.

Moving on, Uncovered: Tales of the Naked Theatre (Samayo Ageha: Mitsu tsubo torotoro), focuses on an acting troupe named – funnily enough – “Naked Desire”, who perform classic tales such as Don Quixote and Madame Butterfly, almost completely in the buff to an audience you could count on one hand. When the director of the troupe, Tsubasa (Ren), adds a new addition to the cast in the form of a shy novice, Ageha (Rino Mizuki), he his met with vocal discord from his entire cast, who systematically take out their frustrations on the young woman.

If the above sounds grim, well, it is. The narrative is rarely anything other than mean-spirited – a bit of a rape-fest if you will – which means that your enjoyment mileage may vary. Granted, there’s an inkling of a message trying to get out, but when you consistently punish your protagonist to the point that you expect her to have a mental breakdown, it’s difficult not to feel complete apathy.

Nonetheless, to keep on point, there are fleeting moments of brilliance. The production values here can’t quite match that of Naked Desire, which was released a year prior, but then again it faces entirely different challenges altogether, which its director seems all-too-adept at handling. Sakaki does a solid job of utilising all the tools in his kit; the inclusion of what appears to be multi-camera set-ups on few occasions (noticeably during an early gathering in which a conversation is in full bloom) provides a rare treat, while the feature’s intimate surroundings, taking place primarily at a shoddy little theatre that barely has a curtain to its name, impresses the most. Using some creativity to illustrate the hardships of a struggling actor’s life, with simple lighting and sparse staging, it’s a solid example of making do with what you have at your disposal – a key factor given that Pink Film scripts must always be extremely budget conscious.

Unmistakably, the best part of Uncovered boils down to its final few minutes, which begins on a rooftop in the middle of the night and culminates in a twisted orgy of writhing bodies. A crane shot leads to a surreal sexual showdown, which descends into the bowels of Tsubasa’s theatre; a disorienting series of edits, involving under-cranking and jump-cuts, not to mention the consistently bizarre scoring, does a wonderful job of playing up to this strange circus of events, so effective in its tension and unusual trickery that it almost feels at odds with the rest of the picture.

To summarise: Is there indeed a “Pink New Wave” emerging here? Perhaps that’s an answer which is too early to give. While aesthetically we may no longer enjoy that “feeling” of good ol’ 35mm prints, the handover to digital hasn’t impeded the actual quality of filmmaking on offer. Given what small amount of evidence here suggests, time will tell if there are any absolutes, suffice it to say that Pink Film isn’t going anywhere any time soon, and there are always going to be thirsty filmmakers, ready to tackle any obstacles which dare get in their way.

Check the films out for yourself!

-

Dismembered - HD - DOWNLOAD TO OWN

$4.95Maximum quantity exceededMinimum purchase amount of 0 items is Required3423 Left in StockMaximum purchase amount of 3 is allowedDIGITAL DOWNLOAD -

←→

Naked Desire - HD - DOWNLOAD TO OWN

$4.95A crazy mix of societal outcasts spend a weekend together at a house on the beach, what could go wrong?Maximum quantity exceededMinimum purchase amount of 0 items is RequiredDIGITAL DOWNLOADNaked Desire - HD - DOWNLOAD TO OWN

$4.95Successfully Added to your Shopping CartAdding to Cart... -

←→

Uncovered: Tales of the Naked Theater Part 1

$4.95Maximum quantity exceededMinimum purchase amount of 0 items is Required4995 Left in StockMaximum purchase amount of 5000 is allowedDIGITAL DOWNLOADUncovered: Tales of the Naked Theater Part 1

$4.95Successfully Added to your Shopping CartAdding to Cart...

![ANARCHY IN [JA]PANTY](https://www.pinkeiga.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/sddefault-31-324x400.jpg)